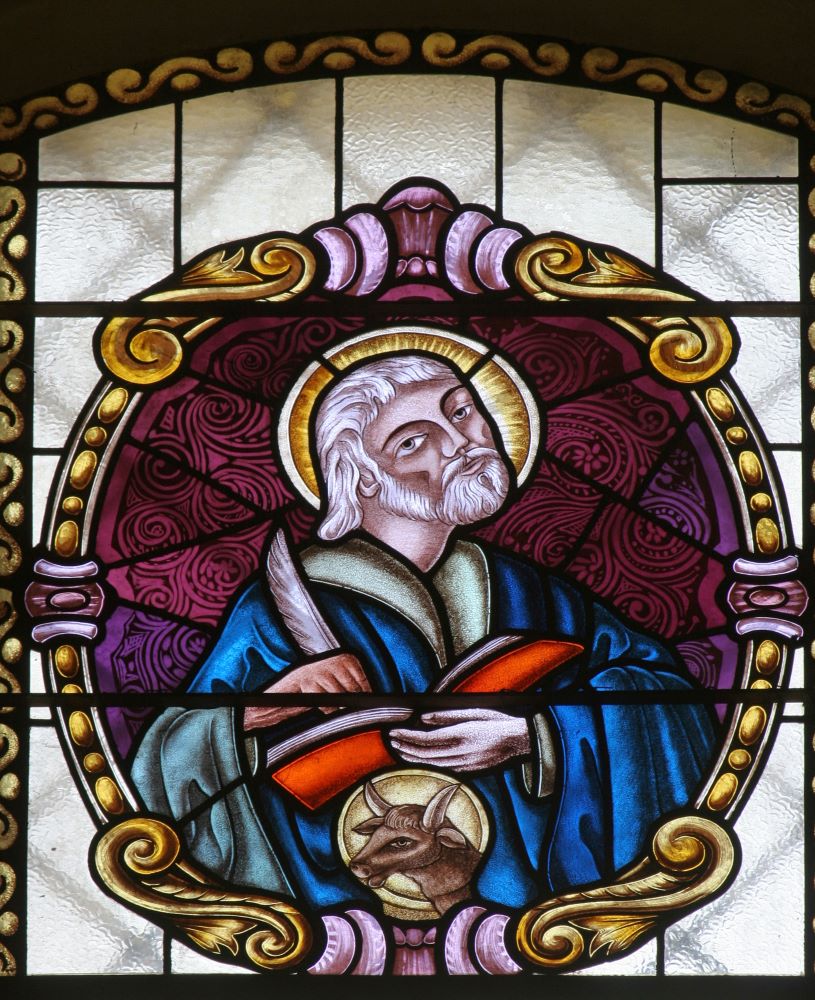

St. Luke (Feast day: October 18th) was one of the 70 Apostles (Luke 10).

He is the author of the Gospel according to Luke. St. Luke was a physician and the first iconographer.

The relics of St. Luke have an interesting history. The miracle-working relics of the Apostle Luke were transported to Constantinople during the 4th-century, under the reign of Emperor Constantius (357 AD), the son of Constantine. In 1204, the Crusaders of the IV Crusade stole the relic from Constantinople and transported it to Padova in Italy and it is still located there in the Catholic church of Santa Justina at the centre of the city.

In 1992, the then Metropolitan Ieronymos of Thebes and Levathia (currently the Archbishop of Greece) requested the return of a “a significant fragment of the relics of St. Luke to be placed on the site where the holy tomb of the Evangelist is located and venerated today”. This prompted a scientific investigation of the relics in Padua, and by numerous lines of empirical evidence confirmed that these were the remains of an individual of Syrian descent who died between 130 and 400 A.D. The Bishop of Padua then delivered to Metropolitan Ieronymos the rib of St. Luke that was closest to his heart to be kept at his tomb in Thebes, Greece.

The tomb works miracles even today. In December 22, 1997 at 1:30 PM myrrh appeared on the tomb’s marble and since then the interior of the marble sarcophagus is fragrant.

In our church, we have the relics of St. Luke. The relic was gifted to our parish by our Bishop Benedict (Aleksiychuk).

What Is a Relic?

A relic is a fragment of the body or physical possession of a canonized saint that can help us grow closer to God. Relics are divided into three classifications. A first class relic is a body part of a saint, such as bone, blood, or flesh. Second class relics are possessions that a saint owned, and third class relics are objects that have been touched to a first or second class relic or the saint has touched him or herself.

Veneration, or an act of honor or respect (not worship), of relics from martyrs dates back to beginnings of the Church.

In fact, churches were often built on the remains of Christian martyrs and current saints to provide more blessings.

Worship vs. veneration

We do not worship relics. Instead, we venerate them. We take great care to distinguish veneration (Greek: doulia) from worship (Greek: latreia). In English, the two words have definitions people often treat as synonymous. However, in Greek, the official liturgical language of the Early Church, the two words have entirely separate meanings. Where worship means completely giving over oneself to service to God, veneration means simply treating something with reverence, respect, and honor. We afford both worship and veneration to God, but the only One we worship is God.

Why do we venerate relics?

The Orthodox Christian practice of venerating relics reflects our beliefs of salvation. We understand salvation as theosis, or deification, becoming “partakers of the divine nature” (2 Peter 1:4). This is the primary reason the Incarnation happened, and why Christ voluntarily endured crucifixion and death. He did this so we could become by Grace what God is by nature. Our bodies are not prisons for our souls, but rather are temples of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 3:16-17; 6:15, 19; Eph. 2:19-22). Thus, God’s grace affects not only the spirit, but also the physical body. This is especially the case for Saints, who actively participate in God’s divine nature (“Saint” comes from the Greek hagiosis, which means, “the holy ones”).

We venerate the relics of saints for several reasons: First, because we believe the body remains the temple of the Holy Spirit, even after death. Second, because veneration of a saint’s relics affirms the reality of his or her existence. Third, the act of veneration communicates that all Christians, even those who have departed this life, remain in communion with God and with one another. Lastly, we do this to honor these saints as examples for how we should live our own lives to please God and achieve theosis. We also venerate their relics in the hope that we may somehow participate in the Grace they received. In other words, to have a share in their holiness.

Where’s the biblical evidence for relics?

In Eastern Tradition, we adhere to the Old Testament as the basis for many aspects of our liturgical worship, including the veneration of relics. We see the ancient Israelites venerating relics and paying them incredible respect, so as Eastern Christians we continue to do the same. The book of Exodus perhaps provides us with the best example: the Ark of the Covenant. For the Israelites, the Ark was the center of all formal worship and was kept in the Holy of Holies. All pious Jews held the Ark in great reverence, and were not allowed to touch it without God’s express permission. Why? Because the Glory of the Lord rested upon it, and within it, Aaron placed relics from the Exodus out of Egypt: a jar of manna (Exodus 16:33); the Decalogue or Ten Commandments (cf. Exodus 25:16; Deut. 10:1-5); and Aaron’s rod (Numbers 17:10).

Elsewhere in the Scriptures, we see the bones of Elisha bring a dead man back to life (4 Kings 13:21), handkerchiefs and aprons touched by Saint Paul healing the sick (Acts 19:11-12), and Saint Peter’s shadow passing over the sick and healing them (Acts 5:14-15). And in the Gospels, many healings involve relics, including the healing of the woman with an issue of blood, who simply touched the hem of Christ’s garment and received healing (Matthew 9:20-22, Mark 5:25-34, Luke 8:43-48. His garment effectively became an avenue of Grace (God’s energy/power) into her (Luke 8:46).